Bursars are well-known for having too much in their in-trays: and now, out of a silicon sky, plonks AI on top of the heaving pile. It’s enough to make the in-tray’s metal struts start to buckle.

Who to believe about AI? Some say the stuff is all a storm in a teacup, no big deal, a bit like smart boards – expensive and overhyped. Boris Johnson (remember him?) meanwhile thought it was the route he took when visiting his levelling up areas in the north-east.

Others say it’s going to change the face of the known universe. They tell us that every facet of life will be changed by this new technology.

So who is right?

In the short term, it is the first group. But in the long-term, the second. What we don’t know is the rate at which the transition will take place.

All bursars should be aware of Amara’s Law, named after American scientist, Roy Amara, President of the Future Institute: ”humans tend to overestimate the effect of a new technology in the short term, and underestimate the effect in the long term”.

With technologies up to this point in history, the long-term could be 50 to 100 years. Think of the time between James Watt’s discovery of the efficient steam engine in the 1760s and the first passenger-pulling locomotives in the 1820s. Now, the long-term is no longer 50 to 100 years, but, with AI, it could be 5 to 10 years.

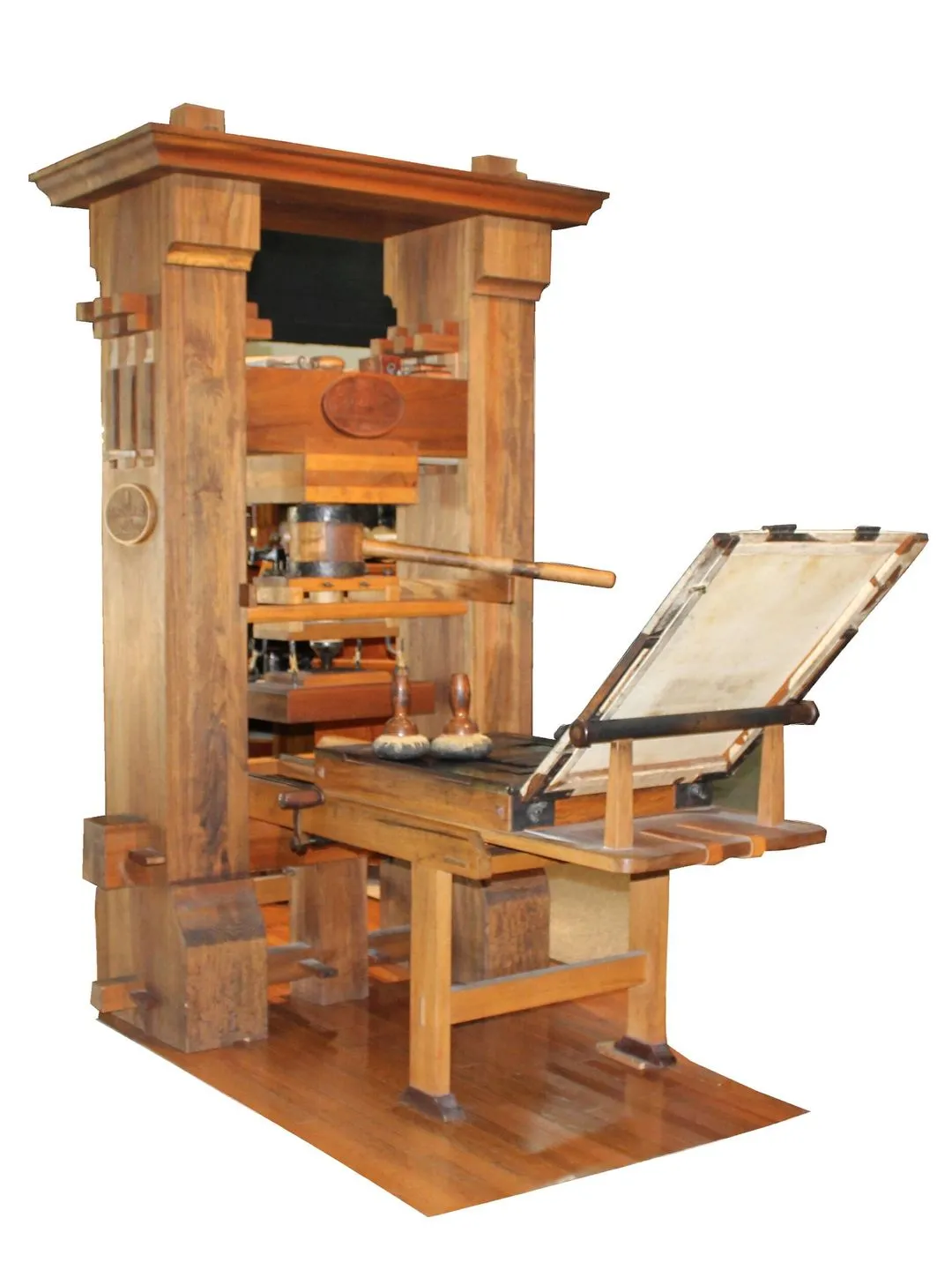

In 2018, I wrote a book The Fourth Education Revolution: Will Liberate or Infantilise Humanity? I said that AI was the biggest shock since the third education revolution 500 years before, sparked by the printing press. It had the potential to ameliorate all five problems that the third revolution had been incapable of resolving in schools:

- stagnant or even declining social mobility;

- students moving forward year by year by age, not stage of understanding, meaning some were left struggling because the work is too difficult, others bored because too easy;

- suffocating teacher workload and stress, because of the heavy administrative workload, which has becomes no easier;

- a narrowing of the offer of schools with ever greater focus on lessons, exams and tests, and less space for the creative arts, sports, character and visits outside;

- and finally, and demonstrably, declining student mental health.

The book explained how AI would address all five of these problems. Oh how people scoffed at the ridiculous claims in the book.

It was even worse than the reception I received 10 years before, when I introduced lessons and activities to improve student well-being.

Now we know about AI. And being an ostrich is no longer sensible or responsible.

To make life easier for bursars, here are my answers to five questions that you might want to know.

1 How big a deal is AI?

The short answer is, massive. Why? Precisely because AI is unlike any earlier technology in history. This is in part due to the latest generation of AI being generative. This new form of AI shot to public attention in early 2023 largely because of ChatGPT which is capable of offering fresh and original content based on analysis of millions, perhaps billions of items of data. Suddenly, everyone was talking about it.

It is not of course thinking in the way that the human brain thinks: it is merely mimicking human intelligence, by processing a vast range of data that no human brain could encompass. It is machine intelligence, not human intelligence. But if we’re not careful, machine intelligence will belittle and infantilise human intelligence.

We are only just in the gentle foothills of the generative AI revolution. In the time it has taken you to read this magazine, generative AI will have improved significantly, at a far quicker rate than any human brain can learn and adapt.

In the past, transformative new technologies, like the printing press, the internal combustion engine, or television, constantly improved - becoming quicker, cheaper, more reliable, and effective – by human intervention. This new AI technology though learns and improves of its own accord. Human beings do not always comprehend what the process is. Artificial intelligence does not need to rest or sleep, it does not become unwell or have moods, it doesn’t throw sickies, and it can process material at vastly quicker speeds than any human being on your staff - or anywhere else in the world. For the first time in history, we have machines that can outsmart us. And that is a big deal. A very big deal.

2 What are the new AI-assisted technologies?

Some websites offering advice, for example, an excellent bulletin produced in September 2023 by a cluster including the NAHT and ASCL, offer a limited notion of AI, seeing its impact primarily on the classroom, and suggesting, rightly or not, that we shouldn’t let ourselves be hexed by what is coming down the track at us. It is certainly right for them to suggest that we should focus attention and spending primarily on teaching and learning this coming academic year. But is there a risk that we can be too timid and, as with the pandemic, fail to invest in new digital technologies that leave students and staff underprepared?

Because AI is not going to move at our speed. We will have to move at its speed. And no one is in control of it. That is why it was vain and misleading for a group of the top leaders in global technology to call in March 2023 for a six-month moratorium on progress on AI. Signatories to the open letter included Tesla CEO Elon Musk, AI pioneers Yoshua Bengio and Stuart Russell, Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, Stability AI CEO Emad Mostaque, and author Yuval Noah Harari. A pause though won’t happen. Think about it. If the west were indeed to halt AI research, would China and North Korea follow suit? AI is taking over from nuclear weapons.

I think it is more helpful to see AI as part of a group of new technologies which, operating together, will profoundly alter schools.

These technologies include:

• Generative AI

• Neuro and cognitive science

• Speech and image recognition

• Virtual reality

• Augmented reality

• Mixed reality

• Internet of things.

• Blockchain

• Big data and data storage

• Transhumanism

• Collaborative learning

• Robotics

• The metaverse

Space precludes a discussion here of how each of these new technologies will transform schools. If any of them are unfamiliar to any reader, the information is just a click away.

3 What aspects of school will be changed?

In brief, every single aspect of school life will be impacted by AI by 2035, if not before. Let us take teaching and learning. This has five principal stages, all of which will be affected.

• Lesson preparation

• Delivery of material to students in a personalised way

• Practical work - including science practicals, drama lessons, sport, and art.

• Marking and assessment of students

• Writing of reports, and assessment of student suitability to pass on to the next level of learning.

Teachers will be able to draw on a far richer and wider range of relevant material when preparing stimulating lessons. The technology will allow every child to benefit from personalised teaching from the AI technology, adjusted to their particular needs, learning difficulties and levels of understanding in each and every subject, and indeed state of mind on the day. Practical work will change out of all recognition: in science, for example, students will be able to conduct experiments far richer and more engrossing than in school laboratories, which are out of reach of many students. Every child will benefit from personalised, formative assessment in real time, so that they can learn far more efficiently from what they are getting right and not getting right. Finally, parents, teachers, tutors, and the students themselves will benefit from personalised, detailed and personal reporting, which will give accurate assessments of progress in each and every subject. A new world.

In addition, it will make an impact on the following aspects of school life:

• Registration

• Student monitoring

• Safeguarding

• Facilities management

• Catering and cleaning

• Maintenance

• Health and safety

• Accounting and finance

• Office admin

• Student and staff well-being

• Human resources

• Relations with suppliers

• Legal aspects

• Governance

• Co-curricular activities

• Parents/guardians relations

Many of these bursarial activities will be enhanced by AI-facilitated technologies. New problems though will also be posed. Schools are currently enmeshed in difficulties over gender. In 10 years’ time or before, AI-enhanced implants will begin to pose a whole new set of moral and legal questions. ‘Get ahead’ is the theme of this article. Don’t be an ostrich.

4. Will Jobs Change Because of AI?

Absolutely not, say the sceptics. They have some justification for their caution. For years, people have been saying that jobs will change. But as of 2023/24, the revolution has yet to happen. But change is coming. One occupation illustrates the point perfectly: London black cab taxi drivers. For years, they took enormous pride and trouble in learning “the knowledge“, i.e. all the streets, landmarks, hotels, and principal destinations across the huge city. Learning it all was a colossal challenge. They took great pride in passing the test, and it contributed enormously to their self-esteem and sense of identity. Scientists reported that the brain mass of London taxi drivers expanded because of the hard work of memory.

But since the advent of AI, all that work has now been made redundant. Passengers would much sooner their cab drivers relied on the AI – facilitated machine on their dashboard to get them to their destination speedily. Worse than that, the knowledge is now actually worse than useless, because it is a handicap. The taxi driver cannot possibly know about a broken down vehicle two blocks away, and the best and quickest route to get round it. Now, had taxi drivers learnt not just the knowledge, but skills of engagement with the different kinds of passengers, they could have been offering a different kind of personalised service too customers, rewarding for both parties. But they haven’t, and most now spend the time instead listening to the radio or talking to friends on their telephones. Are they happier? I don’t know for sure, but my sense is that they feel that their professionalism and skill have been eroded by AI.

Why do I labour the point about London taxi drivers? Because what happened to them will happen across the world of work. Humans will never be able to compete with AI, even in the relatively clunky and imperfect way it operates today. What schools need to be doing is spending more time developing human intelligence in their students, because this is what the world will need: medics who can relate to patients, service industry staff to customers - and politicians to voters. And yes, at the moment, schools continue to regard teachers like machines, showing students how to think more like machines: but we need teachers to work with AI-informed machines to help students learn to be more fully human. Every senior leader in school needs to understand what is happening to employment. There is no space left to be an ostrich.

5. How Should we Respond?

Don’t stick your head in the sand. Until very recently, the Government, specifically the Department for Education, has been doing this, and as a result, it is considered to be behind other countries, including China, Japan, the Baltics, Singapore and Brazil. Equally, don’t be a peacock, parading your own brilliance to the rest of the world, but not sharing what you have discovered.

It is only by collaboration that we are going to get ahead of AI, and ensure that this fourth education revolution is in the interest of all students (and not just the most privileged). The giant tech companies will eat schools for breakfast if we are not careful, as they are already threatening to do to our own lives, knowing far more about us than we care to imagine possible. The dangers are real – abuse of students, appropriation of data, deep fakes and impersonation, cheating, and infantilisation.

Government is now coming up to speed, as is parliament, both aware of the threats and the opportunities. But schools and colleges need to take AI into their own hands: we cannot wait for Parliament and government, and we certainly cannot trust the tech companies.

That is why in May 2023, following a conference at Epsom College, we have set up the Bourne Epsom Protocol (BEP). It uniquely brings together, leading practitioners from across independent and state schools, cutting edge scientists like Lord Rees of Ludlow, the former president of the Royal Society, the heads of the major exam boards, and leading politicians, including former education secretary, Baroness Morgan, former higher education minister, Lord Knight, and chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on AI, Lord Clement Jones. We would encourage everyone to look at this free resource, and contribute to it. It is full of real time advice, practical suggestions and up-to-date information on this rapidly changing field. Please see: https://www.ai-in-education.co.uk/

Sir Anthony Seldon, head of Epsom College, former vice-chancellor of the University of Buckingham, former master of Wellington College, author, political commentator and contemporary historian.